Patrick's course topics include archaeology, history, ancient technology, the arts and literature and frequently fill up quickly. Early enrollment ensures an informative learning experience. Check back frequently as additions and updates are common. Current and Upcoming Courses

THE HISTORY OF WRITING: FROM PICTOGRAPH TO HIEROGLYPH TO ALPHABET

In this course we will explore the history of writing from prehistory on, as writing and language developed to accommodate trade and the exchange of ideas within and between cultures. We will look at questions such as: What does prehistory tells us about the history of writing? How closely related are Mediterranean alphabets around 800 BCE? How did expanding land and sea transportation propel the development of languages in new directions? We’ll explore ancient systems such as Egyptian hieroglyphs; Mesopotamian cuneiform; Ugaritic-Phoenician-Hebrew relatives; classical Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Latin; and Runic writing. We’ll also highlight principles of language evolution, as well as exciting moments in the history of decoding ancient languages, including the discovery and deciphering of the Rosetta Stone, the Behistun Stone, and tablets from the Royal Assyrian library at Nineveh.

Spring Quarter, 2016 Stanford

TEN GREAT BATTLES OF ANTIQUITY

CLA 131

Why are some ancient battles more important than others? History has often pivoted on single battles or the perceptions that result from them. These clashes of empires from Bronze Age Egypt through Babylonians, Assyrians, Greeks, Persians and to the Romans include decisive or memorable battles from Qadesh (1274 BCE), Nineveh (612 BCE), Thermopylae (480 BCE ), Marathon (490 BCE), Issus (333 BCE), Cannae (316 BCE), Cartagena (209 BCE), Alesia (52 BCE), Actium (31 BCE ) to Masada (73 CE). Sometimes the myths that developed from these battlesdrove cultural memory unto the modern era. Placed in the larger contexts of surrounding wars in which they took place, these ten battles are also significant for strategy, tactics and often brilliant military command that exploited enemy weakness, brashness or overambitious perceptions to great advantage.

Winter Quarter, 2016 Stanford

ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANCIENT ENGINEERING

|

|

Large-scale and small-scale engineering in the ancient world offer fascinating parallels to modern technology. How were the pyramids of ancient Egypt constructed? How did the Romans create a hydrology system with extensive aqueducts, and over 50,000 |

miles of roads in Europe alone with many surviving bridges? What is the evolution of ancient optics from Egypt to the Renaissance and then Galileo? What are the qanats of ancient Persia and how did they irrigate Near Eastern deserts? How did the ancient Chinese measure earthquakes and make discoveries in metallurgy? What was the great hydrology system of ancient Peru where the Moche watered coastal deserts with Andean water? These are some of the topics covered in this course, demonstrating that human ingenuity has innovated great technological changes through independent discovery and diffusion.

ARC 122 Stanford Online Course Winter 2016

CELTS, FRANKS, AND VIKINGS

CORNERSTONE CULTURES 2 - ARC 42

Northern Europe has a different cultural background than the Mediterranean we examined earlier in this course series. Uncovering underlying cultures north of the Mediterranean we see Celts, Franks and Vikings who peopled Northern Europe in unique ways. First, from around 800 BCE, Celts who originally came from what is now Austria left legacies that remain into modernity, surviving Rome’s collapse and ultimately migrating into Ireland and Wales and elsewhere. Celtic customs, language, bardic epics and art retain some of the hallmarks that even Romans like Tacitus noted millennia past about the Celts’ celebrations and wearing mustaches and plaid clothes, long influencing Gallic custom and even Scottish tartans. Arthurian legends and chivalry also need grounding in Celtic values and traditions. Second, Franks coming from east of what is now Germany unified Europe with a medieval genius for administration begun by Charlemagne. The Frankish legacy also continues in modern European nations inheriting the imprint of the Carolingian Renaissance in major countries like France and Germany. Lastly, Vikings speaking Old Norse came from Baltic Scandinavia where they were robustly changed Northern Europe through seafaring, shrewd trade and conquest when necessary, including through their Norman descendants like William the Conqueror. In this course we study how these cultures contributed greatly to European heritage.

Spring Quarter, 2015 Stanford

MINOANS, MYCENAEANS, ETRUSCANS, CORNERSTONE CULTURES 2 - ARC 41

When the Greeks tell their own history, they look back to older cultures that were mostly gone but not forgotten. Mythology is the clearest example of this: the stories from Homer onward often take place in a past Aegean world that includes Minoan Crete. Greek heroes also trace back to Minoan and Mycenaean epics of the Bronze Age. Greek religion, architecture and language also retain these traces. Similarly, the Romans absorbed much from the Etruscans before them, again including language, architecture and a whole system of divination and omens, among many other cultural hallmarks that are more Etruscan than the Romans might have wanted to admit. This is a new course of nine lectures and a museum visit.

Winter Quarter, 2015 Stanford

ANCIENT NEAR EAST: SUMERIANS, ELAMITES, HITTITES, CORNERSTONE CULTURES 1- ARC 40

This new course explores the earlier background of the Ancient Near East and examines the mother cultures from which others grew. Between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and Anatolia, three early cultures emerged from different environments to shape the Ancient Near East. One of the first of these cornerstone cultures - the Sumerians - developed in Mesopotamia around the late 4th millennium BCE. The Elamites began in the Zagros highlands of what is now Iran circa 3000 BCE. The Hittites emerged in Anatolia as a formative Bronze Age (2000–1300 BCE) and then first millennium Iron Age culture that ruled what is now Turkey. This is a ten week course.

Fall Quarter, 2014 Stanford

EGYPTIAN ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY - ARC 14

Egypt remains fascinating thousands of years after its ancient voice faded away in the desert; its ruined architecture awed Greek travelers, Roman colonists and every following culture to the present. Archaeologists and historians have a term for this almost obsessive interest: “Egyptomania”, a desire to understand Egypt because many of its secrets and mysteries still endure along with its monuments and a legacy that has influenced so much subsequent civilization. This is a six-week course plus museum visit.

July 2-30, 2014 Stanford

GREAT INVENTORS AND INVENTIONS OF THE ANCIENT WORLD - CLA 46

Global revolutions in technology occur in cycles, often when necessity pushes great minds to innovate or adapt existing tools, as happened when humans first started using stone tools and gradually improved them, often incrementally, over tens of thousands of years.

In this third course examining the greats of the ancient world, we take a close look at inventions and their inventors (some of whom might be more legendary than actually known), such as vizier Imhotep of early dynastic Egypt, who is said to have built the first pyramid, and King Gudea of Lagash, who is credited with developing the Mesopotamian irrigation canals. Other somewhat better-known figures are Glaucus of Chios, a metallurgist sculptor who possibly invented welding; pioneering astronomer Aristarchus of Samos; engineering genius Archimedes of Siracusa; Hipparchus of Rhodes, who made celestial globes depicting the stars; Ctesibius of Alexandria, who invented hydraulic water organs; and Hero of Alexandria, who made steam engines. Some ancient inventors are also anonymous, such as the creator of the Baghdad Battery in ancient Parthia. Then there are the fascinating but quasi-mythical inventors such as flying pioneer Daedalus and Hyperbius of Corinth, who, according to legend, invented the potter’s wheel. As the course moves along, we will also see how these mechanical innovators came up with inventions that changed the arc of history, improved human lives, and made an indelible mark on their own civilizations.

Greats of the Ancient World

This is a year long series of Stanford courses beginning in Fall 2013. The first course in the sequence is on Great Military Leaders (e.g., Cyrus, Alexander, Hannibal) followed by Great Thinkers (e.g., Confucius, Solon, Plato, Lucretius) and then Great Inventors (e.g., Archimedes, Heron).

Great Thinkers of the Ancient World

In this course, students will explore great thinkers who changed the ways people thought in antiquity. Whether philosophers, scientists, poets, playwrights, or even rulers, the figures selected here are credited with major innovative ideas. Confucius’ Analects posed paradoxes about life and its meaning in metaphorical language. Moses articulated monotheism and the folly of representing deity in physical images. Solon transformed Athenian ideas of justice, creating just punishments that fit the crime, a departure from the Draconian punishments that were commonly meted out in the ancient world. Sophocles’ tragic dramas explored concepts of individual destiny and a psychology of self-knowledge, while Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle shifted the way the ancients thought about education, and Lucretius and Virgil wrote epics (De Rerum Natura and the Aeneid) that changed the literary landscape. On the scientific front, Galen wrote voluminous medical texts that laid the foundations for psychiatry and new health praxes. Meanwhile, Jabir Ibn Hayyan (Geber) and Al-Haytham set forth principles of physics, chemistry, and astronomy. These are some of the many thinkers who blazed creative paths in literature, science, philosophy, and politics. In this course, students will delve into the rich intellectual history of the ancient world and see how one great idea could give rise to another—many of which we are still living with today.

CLA-45 Winter Quarter, Wednesdays, Jan-Mar 2014

Great Military Leaders of the Ancient World

Military leaders who changed history through their military prowess and their refined sense of strategy are the subject of the first course in this series. These impressive figures include Cyrus, who created

the Persian Empire from the deserts of Iran to the Mediterranean; Alexander the Great, who conquered western Asia to mediate East and West; and Hannibal, who brilliantly implemented a surprising military strategy that eventually gave rise to the professional

Roman army. Elsewhere we have Qinshihuangdi, who brutally unified China for the first time; Julius Caesar, who anticipated the foundations of Roman emperorship through his conquest of Gaul and his interpretation of power; and Marcus Agrippa, whose victories engineered the achievements and Pax Romana of Augustus. Finally,

we will examine Attila, who unified the barbarian Huns against Rome; Belisarius, who was key to Justinian’s reign; and Charlemagne, who organized the Franks to bring Europe from the Dark Ages to the premodern state. Each historic leader will be biographically

presented, and the course will try to explain the most likely reasons for their successes, drawing on both current research and accounts written during the time these leaders ruled.

Fall 2013 Stanford CSP

Archaeology and Ancient Engineering (ARC 122)

Many of the world’s famous monumental and staggering engineering projects or inventions are in fact ancient, some even prehistoric. Stonehenge and related megaliths date back thousands of years. Found off Greece in a shipwreck, the enigmatic Antikythera bronze is an astonishing invention dating before the Roman empire. Even if Hero of Alexandria’s (1st century ce) steam engines were only theoretical, they deserve mention alongside his pneumatics and mechanics innovations. Some of the most remarkable achievements in antiquity include Roman roads, bridges, the advent of concrete, and hydrological technology such as aqueducts. Add to this the qanat canals and irrigation system of Persia, the pyramids of Egypt, the stone cities and road networks of the Incas and their ancestors in South America, and the urban and sculptural stoneworking of the Aztecs in Central America. All of these feats of engineering, occurring long before the Industrial Revolution, will be the subject of this course.

Summer 2013 Stanford CSP

Mesoamerica: Cradles of Civilization III

In our third course in the “Cradles of Civilization” sequence, Mesoamerica and the New World will stand out as great foundations of culture. Our look at American civilizations will start out 3,000 years ago with the Olmec, followed by the Teotihuacán, Zapotec, Maya, and Mexica-Aztec, as well as the Wari and Inca.

|

|

In some chronological sequence, we will examine important Olmec sites such as San Lorenzo and La Venta, along with Monte Alban in Oaxaca. The Maya sites of Tikal, Copan, and Palenque will be included along with Teotihuacán and Cuicuilco, and Aztec-Nahuatl sites such as Tenochtitlan. In the Andean South American region, we will examine the representative sites of Tiwanaku, Piquillacta, Cuzco, and Machu Picchu, among others. |

Inevitably, the course will cover the devastating impact of the Spanish Conquest on indigenous peoples and their cultural heritages by examining the ethnography of the time. Finally, we will cap off the course with a visit to the de Young Museum where we will see firsthand the great monuments and artifacts that survive the demise of Precolumbian cultures.

Autumn quarter traces Mesopotamian history and archaeology;

winter quarter Mediterranean history and archaeology;

spring quarter Mesoamerican history and archaeology.

Cradles of Civilization

Fall, Winter & Spring Quarters 2012-2013

History evolved out of many places globally over the past seven millennia. For the next three quarters, a sequence of Stanford courses charts three selective epicenters of civilization that contributed major blueprints for human civilization.

Autumn quarter traces Mesopotamian history and archaeology;

winter quarter Mediterranean history and archaeology;

spring quarter Mesoamerican history and archaeology.

Mediterranean: Cradles of Civilization II

In this second course of the “Cradles of Civilization” series, we follow seminal Mesopotamian cultures and move our focus to the Mediterranean, where we will observe developments in Greek, Etruscan, Carthaginian, Celtic, and Roman contexts. We will examine the roots of ancient Greece following the fall of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures and the rise of the Greek polis and city states using ancient source texts and archaeological remains. We will also take a close look at the spread of Hellenizing culture through trade and colonization across the Mediterranean. The Etruscans, Carthaginians, and Celts will also factor into our historical and archaeological overview leading up to Rome’s growth and ultimate control of the Mediterranean region, demonstrated by such examples as Roman imperium and control of the waterways in Mare nostrum. Finally, we will explore how some of the mythic-historical accounts—for example, in Herodotus, Virgil, and Livy—reveal glimpses of how these various cultures perceived themselves.

|

History evolved out of many places globally over the past seven millennia. For the next three quarters, a sequence of Stanford courses charts three selective epicenters of civilization that contributed major blueprints for human civilization.

Autumn quarter traces Mesopotamian history and archaeology;

winter quarter Mediterranean history and archaeology;

spring quarter Mesoamerican history and archaeology.

Mesopotamia: Cradles of Civilization I

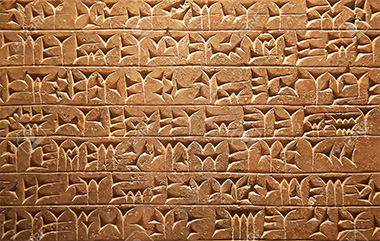

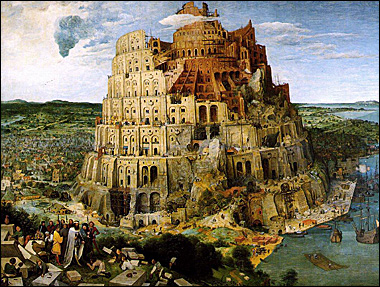

Mesopotamia was the land basin between the two rivers, Tigris and Euphrates, one of the first places civilization emerged about seven thousand years ago. Here scribes first began documenting agriculture and society in gradually more and more sophisticated cuneiform texts. Clay was both the medium of writing as well as the primary medium of architecture. Clay was ubiquitous because the land itself was an alluvial plain and building stone was scarce. Astronomy also greatly developed in Mesopotamia in response to the agricultural and yearly calendar of planting and harvesting to seasonal stars and constellations, lore which also became part of religious life. Legends, cosmologies and law codes from, for example, the Epic of Gilgamesh, Dilmun and Eden, Inanna texts, the Code of Hammurabi to the Tower of Babel and other texts are each consonant in many ways with the archaeological record.

This ten-week illustrated course covers from the seventh millennium BCE with Ubaid and Uruk culture to subsequent Sumer, Akkadia (Agade) and Neo-Sumer, Old Babylon and Old Assyria, Kassite and Middle Elamite, Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian and Medo-Persian and Achaemenid cultures to the fourth century BCE. Students attend lectures, read ancient and modern texts and also visit at least one local museum to better understand the material history via archaeological artifacts.

Archaeology and Art of Sicily

ARC 15 Summer June 27 - August 1

Sicily is the largest and loveliest island in the Mediterranean as well as the most culturally rich. It sits at the crossroads of many cultures that colonized it throughout the millennia, from the Phoenicians onward. Sicily’s art and architecture, not surprisingly, include some of the best surviving Greek temples and theaters, Roman villas and mosaics, Islamic structures, Byzantine churches, Norman palaces, Baroque cathedrals, and of course, remarkable Caravaggio and Antonella da Messina paintings.

In addition, Sicily might be one locus of Homeric myths: Scylla and Charybdis, the Cyclops Polyphemus on Mount Etna, and the nymph Arethusa. Some of the finest archaeological museums in the world are found at Palermo, Siracusa, and Agrigento. Sicily’s riches are relatively unknown to most people, and greater familiarity with its cultural, archaeological, and art treasures is overdue. This course treats Sicily chronologically through almost four millennia via the cultures that have left indelible reminders of their past along its beautiful coastlines, fertile valleys, and rugged mountains.

Stanford University

The Bible Uncensored: What They Couldn't Teach You in Catechism or Your Synagogue - Winter 2012

|

|

|

For a book revered as sacred scripture, the Bible has some of the most

scandalous stories in world literature. Bloodshed, intrigue,

temptation, jealousy, betrayal, lies and the baser human instincts are

common portrayals. One consistent theme is that the greatest sinners

have always made the greatest saints. Moses and David were more like

us than we are often led to believe and their respective angers and

lusts are not hidden from us.

Good literature always tells the truth about humans. Here we read and

learn many new insights about being kicked out of the Garden of Eden,

Cain and Abel, Dinah and Judah, Moses, Rahab the Harlot, the

Shibboleth, Saul and the Witch of Endor, David and Bathsheba, Amnon

and his sister Tamar, Absalom, Solomon's Harem, as well as Peter, Paul

and Mary [Magdalene, that is] and spooky screamers who lived in

graveyards rattling their chains. Some of these shockers make The

Scarlet Letter look tame and Halloween movies look silly. Why else

need salvation?

Winter 2012

HISTORY OF WINE - SPRING 2012 (May-June)

This six week Stanford CSP course is offered in spring 2012 on the history of wine begins in the Neolithic Near East in present-day Iran and continues in Anatolia, ancient Egypt, Minoan Crete, ancient Greece and Rome to the Medieval and Renaissance period to the present day and the New World. Course material is presented through science, history, literature and art. The making of champagne and sparkling wine is also presented along with some wine tasting of contemporary wines.

ROME VISUALIZED

|

|

The story of Rome can be told in many ways. One way that Romans shared that story is through visual art. Virgil, Ovid, and others framed the mythology of early Rome through literature and history, and soon enough their works were also visualized |

in painting, mosaic, sculpture, and other media. This course traces the ways that literature and history coalesced with art to weave Roman foundation myths into an eternal fabric cherished by Western culture. We will take a close look at Virgil’s Aeneid and Ovid’s Metamorphoses and how they created founding myths to visualize Rome. We will then look at striking Roman art, including wall paintings found at Pompeii, which illustrate how quickly the mythology of Virgil’s poem found its way into Roman painting and sculpture. Later, we will see how these Roman myths have lived on in European art and literature. We will study a wide range of European artists including Dürer, Cranach, Rembrandt, Dore, Klimt, and Waterhouse, and also spend time with Dante’s Inferno, seeing how the artists responded with their own individual genius to the Roman imagination.

Spring 2011

(CLA 125)

Wednesdays, 7:00 - 8:50 pm

10 weeks, March 30 - June 1

Alpine Archaeology - FALL 2011

This course emphasizes the unique practices of conducting archaeology in the Alps and montane, high altitude regions while also covering global practices. Topics include geomorphology, montane ecology and paleoclimatology and how these help determine the ancient alpine environment

impacted by humans over millennia. Alpine megaliths and calendrical monuments are also covered along with the discovery of Otzi the Ice Man, a Neolithic human frozen in a glacier for 5,000 years.

This is also a hands-on course where students handle artifacts including stone, metal, ceramics, textiles, glass and other materials. Students learn how to recognize and read ancient coins from Greek, Celtic and Roman cultures as well as how to reconstruct substantial history of a ceramic vessel from a broken potsherd. Students also experiment with stone working and selection criteria for artifacts along with gold working and learning a portable lab for petrography (stone in thin section) for tracing archaeological stone to its geological source, as well as estimate stone weathering through different environments. Labs include archaeological materials, stone working, ceramic technology, gold working, numismatics (coins), lichenization, among others.

ANTHR 60A

3-5 credits M / W 10-11:30

HELLENISM: THE LEGACY OF

ALEXANDER THE GREAT

|

|

The Greeks profoundly changed the world several times in antiquity, first in their own sphere of influence before 400 BCE in the Hellenic Greek-speaking world, and second after they encountered older non– Greek-speaking cultures of the East during and after Alexander the Great. This second period, commencing around 330 bce, is often called Hellenism, and it witnessed the spread of Greek culture to Egypt and Mesopotamia (among other places) and their reciprocal influence on Ancient Greece. |

Alexander the Great from Battle of Issus mosaic (M. Harrsch)

This course will focus on the Hellenistic Age and pay particular attention to the brilliant contributions in science, mathematics, philosophy, and literature that occurred during this period. These contributions came not just out of Athens but also out of Greek colonies and new cities such as Siracusa, city of the brilliant Archimedes, and Alexandria in Egypt, the first true cosmopolis of the ancient world. Alexandria was a magnet for scholars, encyclopedists, historians, poets, and theologians, among others. The city gave us the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures that later proved important for the development of early Christianity. This city also housed the famous Library of Alexandria, an intellectual hallmark of the Hellenistic period, which brought a massive body of ancient knowledge and literature into one location.

Winter 2011

(CLA 124)

Wednesdays, 7:00 - 9:00 pm

10 weeks, January 12 - March 15

Stanford University

SLEUTHING CARAVAGGIO

|

|

Caravaggio (1571–1610) was the most revolutionary artist of the Italian Baroque, transforming art forever with his natural realism and chiaroscuro style. Consistently emphasizing the humanity of his religious subjects, whether sinners or saints or both, he established a new canon. Since 2010 is the 400th anniversary of his death, Caravaggio is being celebrated this year with global exhibitions of his pioneering work. |

The drama of his artistic rise and fall will be a main topic of this timely course. We will chart the career of this phenomenal genius whose brief life was as intense as his art. Many contrasting interpretations of Caravaggio present him as a genius, outlaw, heretic, murderer, and sensualist — but, above all, the vanguard painter of the Baroque Era. Given the paucity of verifiable biographical documents, Caravaggio the artist and Caravaggio the man are often equally mysterious and elusive to modern admirers of his 100 marvelous paintings produced between 1593 and 1610. This seventeen-year period will be a major focus of this course.

Fall 2010

(ARTH 240)

Wednesdays, 7:00 - 8:50 pm

10 weeks, September 22 - December 1

Stanford University

Medieval Art and Archaeology

|

|

The Middle Ages were more than just the Age of Faith and incredible, soaring cathedrals. They were also times of great artistic and intellectual foment, but noted as well for feudalism in both castles and walled cities and ultimately the advent of gunpowder that made such castles obsolete, reducing them to expensive follies. |

Especially from Charlemagne onward, beautiful manuscripts were produced by hand in abundance until the rise of the printing press.

In this course we examine the treasure trove of artistic, architectural, and archaeological material that has survived to the present day from the immensely rich cultural heritage of the European Middle Ages. This course will move from exquisite art and stunning architectural projects (cathedrals and castles) to delicate handwork (ivory carving); from sacred art (manuscript illumination) to the secular arts of war (chased armor and heraldry) and luxurious textiles (tapestries). The Middle Ages has been romantically revived many times over the past 200 years, most notably in Great Britain by Sir Walter Scott and William Morris, and by Viollet-le-Duc in France. While not dismissing completely their portraits of the medieval period, we will look closely at the findings of recent archaeology and try to reach a more balanced assessment of the accomplishments of what must be considered one of the dazzling pinnacles of European cultural achievement.

Spring 2010

Wednesdays, Spring Quarter, Stanford University

Winter 2010

Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

|

|

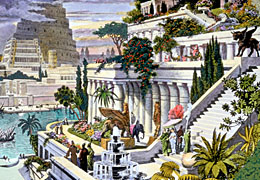

Lists of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were originally compiled in antiquity for astonishing engineering works that almost defied description —some of the monuments were referred to as early as the 5th century BCE by |

Herodotus. By the Roman period, geographers, travelers, and historians agreed on seven wonders that “topped” the list: the Great Pyramids of Egypt, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, the Temple of Artemis Diana at Ephesus, the Lighthouse of Pharos at Alexandria, the Colossus of Rhodes, and the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. Archaeologists and historians have since looked at these often-romanticized wonders— whether or not they survived to the present—as expressions of religion, mythology, art, power, and science. This course, we examines a range of “wonders” as well as two slightly later Roman works that many think should belong on this list—the Pantheon in Rome and the Pont du Gard aqueduct in Provence.

Stanford University – Winter Quarter 2010 - ARC 109

Wednesdays, Jan. 13 – Mar. 17

This has also been a Stanfod University undergraduate and graduate student summer course.

Previously Offered Courses

Medicine in the Ancient World June-July 2009

|

|

Ancient medicine sometimes appears surprisingly similar to modern medicine. At other times, it

exposes what we regard as deep superstition and ignorance. The ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians,

Greeks, Romans, and other cultures often asked similar questions to the |

ones we pose about health and disease today. And they began developing surgical processes that still exist in some form, while also practicing pharmaceutical and psychiatric approaches that we can recognize in modern science. This course offers a survey of ancient medicine, looking at both ancient cultures and pioneering individuals. Here we will encounter ancient doctors such as Hippocrates, Celsus, Dioscorides, and Galen and also explore important texts (including De Materia Medica) and ancient medical instruments that have been preserved from Pompeii to Northern Europe. Memphis, Babylon, Alexandria, Cos, Pergamon, and Epidaurus are only a few of the places we will study where ancient medicine had a long and successful tradition."

Summer 2009

Wednesdays: 7:00 - 8:50 pm

6 weeks:

June 24 - July 29

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Classical Mystery Cults of the Greco-Roman World - Spring 2009

|

|

The great cult and mystery of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis, the Mysteries of Dionysus, the Mithraic Mysteries, the mysteries of Isis, and the mysteries of Cybele-Attis all competed in the Classical world for the souls and wealth of |

people from Roman Europe in the West, to Egypt and the Near East. The rites of these mystery cults, which offered advantages such as community and salvific hope to their members, were generally not meant to be shared with the uninitiated.

| Nonetheless, during its early rise, Christianity could not escape the influence of these mystery cults, and the new religion subtly assimilated their praxes in an "if you can’t beat them, join them" philosophy. Eventually, by the late 4th century, Christianity would solidify its hold on Europe and the mystery religions would be outlawed by Roman emperors such as Theodosius and gradually fade into history. In this course, we will recover these religions that organized and gave meaning to ancient life. |

|

|

(CLA 117)

Spring 2009

Wednesdays: 7:00 - 8:50 pm

5 weeks:

May 6 - June 3

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Archaeology and Art of Persia - From Cyrus the Great to the Ottomans - Fall, 2008

|

|

Persia has had one of the longest, most glorious and fascinating histories in the world. Too often neglected by the West, Persia has |

a wealth of culture and has made immense contributions to civilization jealously admired and acknowledged by the ancient Greeks and the later Byzantines at least from Cyrus the Great around the 6th c. BCE all the way through the Ottoman perod in the 19th century. Its legendary arts and architectural sites range from Achaeminid Persepolis to Safavid Tabriz and Isfahan with great monuments, rich textiles, intricate miniature paintings, ceramics and perfumed gardens. Its jeweled metalworking include such materials as the fabulous Oxus Treasure Hoard discovered in the 19th c. and its great literature includes the epic SHAHNAMEH (Book of Kings) to the Tales of Rustam, the medieval Persian Hero. These are only a few highlights covered in the course.

Fall 2008

Sept. 24-Dec. 3, Wed. eve.

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Plundered Art: From Nebuchadnezzar to Nero, Napoleon and the Nazis

Summer 2008 - ARTH 218 (June 25 to July 23)

|

|

In recent years, many leading museums have found themselves at the

center

of controversies focusing on whether they have developed their

antiquities collections unethically. |

This course focuses on the ethics of art collecting and offers historic examples of plundering from

Nebuchadnezzar to the Nazis. The theft of art is hardly a modern

phenomenon. Verres, a greedy Roman

governor of Sicily, illegally amassed astonishing stolen civic

treasures. The Roman Emperor Nero robbed Pergamon of its most famous

sculpture of the Hellenistic world, the Laocoon group, and installed it

in his notorious Golden House. The Venetian Sack of Constantinople in

1204, the Conquistadores' sack of Mexico and Peru in the 16th century,

French and British expeditions in Egypt and Mesopotamia all provide

examples of a

trend that lives on today. This can be seen in such examples as the

pillaging of the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad as well as other

sacred Iraqi sites and whether the U.S. is somehow complicit. Our

cultural odyssey following plundered art will be global in nature and

will cover millennia of purloined treasures.

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Art, Archaeology and Myth: Olympian Visions. Layered Meanings

Spring Quarter 2008 (arc 08)

|

|

Centaurs, Gorgons, Sphinxes, and many other myth personae have been

painted and sculpted for thousands of years in Western Art, but what

can we learn from their accumulated layers of meaning? Who and what

were the older models of |

Athena and Demeter going back to the Bronze

Age? How has Aphrodite changed from her earlier archaeological

antecedent in the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar? What meaning does the

caduceus of Hermes possess through time?

How long have myths been

visualized in art? What changes in cultural perception, conventions,

and social values are reflected in the variations of how mythology is

rendered through time? Layers of iconography are shown and analyzed in

this course, which examines known embedded archaeological evidence in

the various arts depicting myth. These and other questions are a few

of the approaches taken. This new course also suggests possible routes

that images take across ancient cultures over millennia to the modern

era, providing possible ways to date the changes in the art of myth

through time.

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Great Lives in History

|

|

How many people in history actually deserve to have their names

described as "great"? Cyrus the Great, Alexander the Great,

Constantine the Great, Charlemagne, Frederick the Great, and Catherine

the Great are a few that immediately spring to mind. These historic

figures earned the designation because they either greatly influenced

history in their day, or they affected humankind afterward. Some

others could be described as great if only because their intimidating

influence was admittedly profound. As such, we have

Nero-the-Not-So-Great, as well as Pope Gregory the Great, William the

Conqueror, and Genghis Khan. |

This course examines ancient and modern lives, using surviving records

and accounts, in order to evaluate or confirm their claims to global

greatness. Along the way, we will take a close look at the official

historical accounts of these lives. And we will also peer into their

tent camps and bedrooms and see these figures from less historically

explored perspectives.

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Hannibal - Spring 2008

|

|

Hannibal is a name that evoked fear among the Romans for decades. His courage, cunning and intrepid march across the Alps in 218 BCE with an army and elephants over snowy crags and dangerous passes are still features of one of the most exciting reads in ancient |

history from Polybius, Livy and Appian, the ancient sources, and continue to inspire historians and archaeologists alike today. The mystery of his exact route is still a topic of debate, one which has consumed Patrick Hunt for over a decade as Director of Stanford’s Alpine Archaeology Project since 1994.

From his childhood in Carthage to following his father Hamilcar to Spain and then facing the enemy Romans with amazing battles which decimated the Roman legions, the life of Hannibal Barca still stands as that of one of the most fascinating and brilliant strategists in history. This course examines Hannibal’s childhood, young soldierly exploits in Spain and follows him over the Pyrenees and into Gaul, the Alps and Italy and beyond, also examining his legacy after the Punic Wars. Patrick Hunt is featured in the winter issue (2006-07) of ARCHAEOLOGY magazine for his Hannibal research and also was featured on the HISTORY CHANNEL (November 6 & 16, 2006) for his work on Punic Carthage and Hannibal. His book on Hannibal will be forthcoming in 2010.

Mon. - Wed. Morning (Jan-March)

Stanford University Classics Dept, Undergraduate Seminar

Top Ten Archaeology Discoveries of the World 2008

|

|

"If any global archaeologist were asked to name the top ten archaeological discoveries that have made the greatest impact on archaeology and history, most lists would be likely to unanimously mention the following huge impact discoveries: the Rosetta Stone, Pompeii, Nineveh, Troy, King Tut's Tomb, Machu Picchu, Thera-Akrotiri, the Dead Sea Scrolls, Olduvai Gorge starting with the Leakey Era and the Tomb of the Ten Thousand Warriors in China. This exciting book, written with a taut narrative, relates the dramatic moments of these discoveries, whether by professional archaeologists or by amateurs' accidents, and highlights their significance to history."

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

10 week course, September-December

Goto: www.tendiscoveries.com. |

Ancient Athletics - Fall 2007

|

|

Many evidences from ancient art and archaeology witness how seriously athleticism was taken as both a personal and communal value within society. The ancient Greeks believed in balancing mind and body where physical training was rigorously accompanied by mental training and vice versa. Few people know Plato's real |

name was Aristokles, since "Plato" was his nickname reputedly given by his wrestling coach and roughly means "broad-shouldered". This course examines the philosophy behind the Greek idea of balance and analyzes the ancient athletic events - footraces, jumping, throwing javelins, chariot races, wrestling, etc., and places like Olympia, Nemea, Isthmia and Delphi, among other city venues, where games and festivals were regularly held. Reconstructions of ancient events will also be attempted.

Mon. - Wed. Morning (September - December)

Classics Dept. Undergraduate Course

Rembrandt: His Life in Art - ARTH 200

|

|

"Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–69) was one of those few genius artists who

achieved fame in his youth only to be nearly abandoned by society in his later life. While ushering in the Dutch Baroque Age at the height of Amsterdam’s glory days in the 17th century, Rembrandt summed up Realism and in some ways anticipated both Romanticism and Impressionism. While he is still considered by some to be the greatest biblical painter of all time, Rembrandt hardly ever went inside a church. |

Never traveling outside of the Dutch culture, he always seemed confident that he would eventually be acknowledged by global posterity as a Great Master. Misunderstood but also mischievous, Rembrandt’s unparalleled work in enduring paintings and engravings speaks best about his life. Four hundred years after his birth, Rembrandt is still celebrated as one of the greatest artists of all time."

The course text for this class will be Patrick Hunt's REMBRANDT (2006) book.

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Wednesday evenings

7:00 - 8:50 pm, 10 weeks

Jan 10 - Mar 14

The Renaissance Retrieval of the Past:

An Archaeology of the Mind - 2007

|

|

The European Renaissance derives its name from the “rebirth” or rediscovery

of ancient cultural models and ideals. Petrarch’s Ad Fontanes, “[Back] to the Fountains,” was the hallmark of the day, as thinkers in all disciplines dipped into the European cultural past for fresh inspiration. |

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 brought a forgotten wealth of ancient lore, along with thousands of refugees, to the West. The humanist Erasmus offered new Greek translations of biblical texts that improved on Jerome’s Latin Vulgate. Around 1300, Giotto and other artists studied extant Etruscan and Roman wall paintings and borrowed their revolutionary perspective. Greek astronomy and mathematics, preserved through Arabic, saw new light of day, as Nicholas Copernicus and Giordano Bruno revived the heliocentric ideas of Aristarchus of Samos. In this course, we will study these and many other topics in art, medicine, physics, geography, and the history of science that reveal the deep debt of the Renaissance to the ancient past.

Autumn Quarter 2006

(HIS 128)

Monday evenings, 7:00 - 8:50 p.m.

Sept 25 - Dec 4, 2006

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Greek Mythology 2004-2007

|

|

How familiar we are with phrases like "Pandora's Box" or "the Labors of Hercules" or "Between a Rock and a Hard Place" or "Siren Song" and many others that have become idioms and metaphors for common expressions in our lives, now illumined in this course. Themes like the Trojan War, the Coming of Spring and the Seasons, The House of Kadmos and Oedipus and the Sphinx, Perseus and Medusa, |

Prometheus Brings Fire, Deukalion and the Flood, Cupid and Psyche, Dionysus and Wine myths, the Loves and Feuds of the Gods, How Zeus, Poseidon and Hades divided the Cosmos between Them, Heroes and Monsters, Pegasus and Chimaira are just a few of the tales and topics in the course. Mythology - even fictive - may treasure kernels of truth about humanity. Patrick Hunt will also assign and share readings from his own unique and original retellings of myth.

GREEK MYTHOLOGY (CLASSGEN 18)

Stanford University, Fall Quarter 2006,

Undergraduate and graduate enrollment

This course is limited to registered students, including from outside Stanford.

Archaeology and Ancient Engineering 2005-2006

|

|

Large-scale and small-scale engineering in the ancient world offer fascinating parallels to modern technology. How were the pyramids of ancient Egypt constructed? How did the Romans create a hydrology system with extensive aqueducts, and over 50,000 |

miles of roads in Europe alone with many surviving bridges? What is the evolution of ancient optics from Egypt to the Renaissance and then Galileo? What are the qanats of ancient Persia and how did they irrigate Near Eastern deserts? How did the ancient Chinese measure earthquakes and make discoveries in metallurgy? What was the great hydrology system of ancient Peru where the Moche watered coastal deserts with Andean water? These are some of the topics covered in this course, demonstrating that human ingenuity has innovated great technological changes through independent discovery and diffusion.

ARC 122 Wed. eves 7-9 July 5 - Aug. 2

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Archaeology and Classical Mythology 2005-2008

|

|

"The great mythologer Joseph Campbell suggested history can be real but not necessarily true whereas mythology is not necessarily real but full of truth. Some of the questions examined in this class are "Can we find kernels of historical truth in mythology as in places such as Troy, Mycenae and Thebes and other archaeological sites?" "How do mythology and archaeology overlap?" |

How did the Greeks understand spring and the cycle of seasons through the myths of Demeter and Persephone?" "How does myth inspire art and where do myth and art converge?" "Are there oceanographic and natural explanations for many Greek monsters?" "How were curses against the dynasties of Oedipus and Agamemnon explanatory for the fall of Thebes and Mycenae?"

ARC-08

Monday evenings

January 9 - March 20, 2006

Stanford University.

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies.

Top Ten Archaeology Discoveries of the World2005

|

|

If an archaeologist were to list the most exciting and seminal archaeological discoveries in the world, nearly every list would include King Tut's Tomb, Machu Picchu, the Rosetta Stone, Pompeii, Akrotiri on Thera, the 10,000 Chinese Tomb Warriors, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Assyrian Library of Ashurbanipul at Nineveh, Troy, and Olduvai Gorge or African Great Rift ancient human ancestors like "Lucy." |

This slide-illustrated, five week course examines each of these discoveries—whether deliberately sought or accidentally found—in the context of an evolving discipline since the 18th century and the intellectual and philosophical climates of the period when they were brought to light. How each of these discoveries changed perceptions of history and the future directions of field research is also part of the course. Subsequent generations of scholars may not agree on the most important archaeological discoveries, but is it likely that the works we study will stand out for archaeologists practicing between 1750 and the present.

Summer 2005 at Stanford University

Offered by Stanford Continuing Studies

|

|

Stanford Continuing Studies offers a broad range of courses, seminars, and workshops, primarily in the liberal arts, designed to enhance the learning and enrich the lives of people in the Bay Area. Learn More.

|